Good Morning,

I’ve always wanted this publication to also cover an exploration of how AI is impacting various kinds of people. As people this means our shared culture, health situations including aging in the human life cycle, the conditions we face, health situations we might find ourselves dealing with, including various groups or individuals that don’t receive adequate coverage of their own needs.

From the impact of AI on our mental health to our spiritual & psychosocial development, Generatie AI has so much potential. I’ve taken it upon myself to try to find guest writers and niche pioneers to help us explore in essays these wide-ranging impacts. This is the first in that series.

If you value these explorations, by sharing you promote an emerging writer (often with a nascent Newsletter) that nobody in the world could fill, but that person.

I asked of the Newsletter Speculative (7 month old Newsletter), specifically to help us understand better the impact of Generative AI on disability.

As a population or demographic ages, the conditions we face and experience also changes. Can AI help with that?

In the United States, more than 1 in 4 adults (28.7%) have a disability, according to the CDC.

According to a 2022 American Community Survey, approximately 44.1 million adults in the United States, which amounts to about 13.4% of the civilian noninstitutionalized population, reported living with a disability.

The most common forms of disability vary by category and severity, impacting individuals in different ways. I think we could conservatively say about one in five American suffers from something that could be called a disability. This is not some vague minority, this is someone in your family, one of your friends or colleagues, someone you know, maybe you in the future!

-

Chronic Health Conditions

-

Mobility Impairment (including 20% of adults 65 years and older)

-

Vision or Hearing Impairment (around 8.4% of the population)

-

Mental Health related conditions

-

Cognitive disabilities (think Autism spectrum disorder or brain-injury)

-

Intellectual disabilities (around 1-3 %)

For example, As of 2024, approximately 1 in 36 children in the United States has been identified with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Or 4% of boys and 1% of girls. Additionally, this increase in prevalence (for a number of reasons) has been noted over the years, with a 312% rise since the year 2000. As of 2024, approximately 60% of adults in the United States live with at least one chronic health condition. As of 2024, about 9.2% of U.S. adults are classified as having severe obesity, which is often referred to as morbid obesity. Suffice to say the continuum of what we might consider disability and how AI might be able to help is also changing.

Anna’s Dallara intro to Speculative

25 seconds

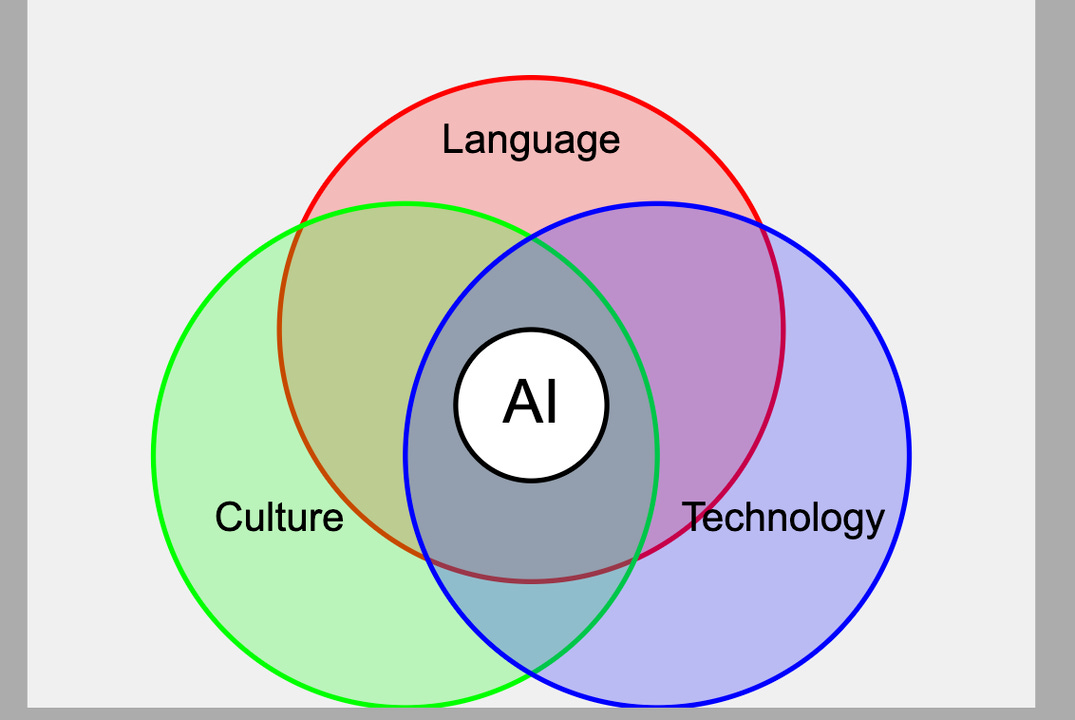

Our guide today, Anna, is a freelancer and product owner based out of Raleigh, North Carolina. She is a Science fiction and fantasy author, excelling in speculative fiction 🗯, a technologist & filmmaker ~ here interested in writing, technology, culture, and where they all intersect.

The way culture and technology are intersecting is becoming more complicated in 2025 affecting people in different and unique ways. – Ed.

I’m hoping you will be able to resonate with today’s topic because it has just massive significance on how AI will impact the human condition, quality of life and providing us with new tools to cope in an ever changing world.

Think about all that this means:

Substack (this platform) itself claims to be a “new economic engine” for culture.

Let’s get into the deep dive.

Explore 🤔💭 Speculative:

💁🏻♀️ reading and writing in the digital age. ⭐

Speculative

-

This wide-ranging essay makes a lot of salient points about disability and AI that is incredibly human.

-

She explores various models of disability, makes many important references, and guides us to explore various tools and strategies.

-

She explores how fundamentally we as people are using Generative AI to self-optimize our lifestyle and help us navigate and deal with our unique challenges, including those somewhat outside of our control.

The AI Will See You Now: Disability in the Age of Chatbots

23 minutes, 6 seconds – Tl;dr, listen instead. 🎧

By of Speculative Newsletter.

Some people start the day by splashing cold water on their faces or brewing a cup of coffee. I roll out of bed and immediately check my Fitbit app to see how well I slept.

I’ve had chronic fatigue since I was sixteen. About six months ago, I decided to prioritize my health for the first time in my adult life. The only problem was that I had no clue where to start. Most doctors gave up when they couldn’t find anything obviously physically wrong with me. I was healthy, just…tired.

So, I started talking to chatbots.

After checking my sleep score, I open the Anthropic app and ramble at Claude (my chatbot of choice). I tell it my score, feelings, and any changes I made in my diet or exercise. Claude listens and offers insights, looking for patterns in my sleep data. Then, it helps me plan my day to balance work with the rest I need.

The Complicated Reality of AI and Disability

Countless people like me struggle with some sort of disability. Some of us are finding relief with the help of this new generation of AI tools. Others worry about the long-term effects AI might have on our lives.

When I was asked to write this article about AI’s impact on disability, I wasn’t sure where to start. Disability is a broad category. Was AI good for disabled people or bad? Who was I to say, anyway?

Ultimately, I can only say, “It’s complicated.” There’s a lot to consider, so I considered as much as possible. I tried to balance the good and bad, the individual and the societal. The truth usually lies somewhere in the middle.

A quick disclaimer: I can’t and don’t speak for everyone. I am one disabled person sharing my own opinions and experiences. You’re welcome to disagree with me. If you feel comfortable, feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

❓ Editor’s Picks for Speculative 🔎

-

Death of the (AI) author?

-

Who gets to be an AI expert? Part 2

-

I’m a disabled writer. Here’s what I think of Nanowrimo’s AI statement.

-

Who gets to be an AI expert? Part 3

What is disability?

According to the CDC, 28.7% of adults in the United States have a disability. The World Heatlh Organization estimates that 1.6 billion people worldwide live with a significant disability. What does that mean?

We’d like to believe that disability is straightforward, a black-and-white category we can sort people into – “If you have a wheelchair, yes…If you graduated from college, no…”). The reality is much more complicated.

Disability isn’t always obvious. Millions of people live with invisible disabilities, which means that you cannot tell they are disabled just by looking at them. Neurodivergence and mental illness are considered disabilities, and even professionals can struggle to spot these.

Disability is also more than a diagnosis (and plenty of people can’t or won’t seek a label). It’s an identity.

A woman I know sank into depression after her husband died, but she didn’t consider herself disabled. For her, the depression was part of her grief. Another person with depression might feel differently. At its core, disability is how you experience your body and the world you move through.

The reality of disability is complicated, and there is no single “disabled experience.” This means there is no one answer to the question, “How will AI affect disabled people?” AI will impact different people in different ways, depending on the exact nature of their disability and their circumstances.

Models of Disability

Conversations about AI and disability go one of two ways:

In one, AI is a hero, fixing problems for disabled people – “Look, here’s an app that can help blind people see! AI is amazing!” In the other, AI is dangerous – “These tools will just reinforce existing bias and make our lives worse!”

After hearing these arguments over and over, I noticed something odd about them. These conversations perfectly fit the two most common models of disability: the Medical Model and the Social Model.

The Medical Model of Disability tells us disability is a medical condition. People with disabilities are patients who exhibit particular symptoms which can be diagnosed, monitored, and treated. In this model, the disabled person is an individual with a problem that needs fixing.

When people call AI the solution to a person’s problems or the treatment for a specific set of symptoms, they speak the language of the Medical Model.

The Social Model of Disability tells a different story. In this view, a person’s body isn’t responsible for their disability – society is. Consider this: If we lived in a world where everyone spoke sign language, being deaf wouldn’t be a disability, and hearing wouldn’t be necessary for communicating.

The Social Model is a backlash against the Medical Model, and its proponents advocate for a more inclusive world with universal accommodations. When people express concern about how AI will make institutions more or less inclusive for disabled people, they are talking about the Social Model.

Both of these models frame discussions about AI and disability. We need to consider both to see the bigger picture.

AI and the Medical Model

Most AI success stories center on the Medical Model. Consider my own success: I’m using a chatbot to track my sleep and plan my recovery.

AI will revolutionize medicine as we know it. That means innovative treatments, accessible resources, and personalized recovery plans.

The revolution has already started. AI tools and treatments are breaking ground in the following areas:

-

Diagnostic assistance

-

Drug design and testing

-

Virtual health assistance

-

Gene sequencing

-

Mental health support

AI is also being used to help people living with specific disabilities, including neurodivergence, blindness, and auditory impairments.

✏️ Support the Author

🧐 About page.

Support for Neurodivergence

Nanowrimo, the nonprofit behind the popular November writing challenge, released a controversial statement about AI last fall: “We believe that to categorically condemn AI would be to ignore classist and ableist issues surrounding the use of the technology,” they said. “Not all brains have the same abilities and not all writers function at the same level of education or proficiency in the language in which they are writing. Some brains and ability levels require outside help or accommodations to achieve certain goals.”

The literary world went wild. Writers accused Nanowrimo of being tone-deaf, supporting “theft” and “plagiarism,” and pandering to tech sponsors. I scrolled through endless outrage on social media for days afterward. At the same time, another conversation took place in the privacy of closed forums and Discord servers I’d joined.

One dyslexic writer said he relied on AI tools to catch grammar and spelling mistakes. A writer with memory difficulties said chatbots helped her remember details of complex plots. An autistic writer said revising with AI helped her overcome communication difficulties so neurotypical readers could understand her.

In other words, Nanowrimo had a point. For some neurodivergent writers, AI greatly improved their ability to write.

This little literary drama hints at a much larger story. AI has incredible potential to help neurodivergent people communicate, plan, and navigate the neurotypical world.

Tools like Goblin AI help people with executive dysfunction break down tasks into manageable steps. The EmoEden app teaches children to recognize and express emotions. A recent study theorized that chatbots could help autistic people communicate, learn social skills, and simulate real-world situations in a lower-stress environment.

Personally, I rely on Claude to plan when my brain fog gets too thick. Scheduling can be time-consuming, and I’d rather save energy for other things.

Assistance for Auditory and Visual Impairments

My grandmother’s hearing aid includes built-in AI features to reduce white noise. She has no trouble following a conversation, even in a crowded restaurant. Features like this are becoming more common in newer hearing aids.

AI can do more than remove white noise. Tools like Microsoft Translation have become adept at real-time captioning in the past few years. Speech recognition and AI narration are improving, making the transition between speech and text easier than ever. Some AI tools can even interpret sign language.

AI has many benefits for blind and low-vision people, too. Be My Eyes is an app that connects blind people with volunteers who can help them “see.” Volunteers take video calls to see what is in front of the blind person and serve as their “eyes.”

It’s a great idea, but there’s just one problem — volunteers aren’t always available. That’s why Be My Eyes launched Be My AI. The AI version of the app analyzes images and descriptions 24/7. The app isn’t perfect (it’s prone to errors and hallucinations, just like any LLM), but the company hopes it will give blind people greater freedom and independence.

Better Research and Advocacy Tools

I could go on for a while, but you get the idea. The latest generation of AI tools has applications for people with all manner of disabilities. And everyone can benefit from better research and advocacy.

Most doctors don’t understand chronic fatigue. They mean well, but they never received proper training around this condition. Other doctors don’t “believe” in it and blame patients for their symptoms.

I’ve had to teach myself most of what I know about managing chronic fatigue. AI search engines like Perplexity make asking questions and fact-checking answers easy. I used to waste hours trawling search results, seeking answers to specific questions. Now, I get what I need in minutes.

The more I know about my condition, the better I can advocate for myself. Before going to the doctor, I use a chatbot to write a medical dossier. I include a complete medical history, previous treatments, and current medications. I brainstorm lists of questions to get the most out of my visit. Claude can even suggest possible treatments or tests to explore with the doctor.

When I arrive at the doctor’s office, I hand over my dossier and steer the conversation towards my questions and treatment options. It’s a small change, just a few pages of info that’s mostly in their charts already. But the difference is profound.

Doctors treat me better now. They talk to me like an equal participant and refer to my dossier during our conversations. They order tests because I request them and are willing to explore options that aren’t immediate or obvious. Because I walk in with an agenda, I get more out of each visit.

At first, I worried I was being a nuisance — advocating for yourself is hard! To my surprise, doctors thanked me for my dossiers. They said it made their jobs easier to see everything laid out. One nurse even congratulated me. “Medicine wasn’t made for women like you and me,” she said. Don’t ever stop standing up for yourself.”

Use at Your Own Risk

Of course, AI isn’t perfect. Chatbots hallucinate, making up false information. Before you trust a chatbot with your health, please make sure it’s telling the truth! A quick Google search usually sorts the truth from the lies.

Chatbots aren’t just lying to you, either. AI can spread misinformation to the general public, increasing stigma and perpetuating stereotypes.

For example, art generators struggle to depict realistic prosthetic limbs. “They perpetuate obnoxious stereotypes about limb loss and disability, reinforcing comic-book caricatures that exaggerate and fetishize bionic enhancements,” say the writers of Amplitude, a magazine for amputees. “Instead of normalizing limb loss, the images turn amputees into superhuman cyborgs, techno-enhanced idols, armored RoboCops — freaks, to use plain language.”

Privacy is also a concern. Some companies store your data to train future models, and bad actors can trick chatbots into divulging personal information.

Before discussing sensitive health issues with a chatbot, I review the company’s privacy policy. I also pay for premium versions of tools whenever I can. If you can afford it, I highly recommend this strategy. You’re paying for privacy.

AI and the Social Model

The Social Model is where things get trickier. We’re talking about society as a whole, not just individual patients. Social systems are complex, entrenched, and biased. Treating one person’s medical problems is easier than fixing all of medicine.

Most critiques of AI and disability focus on the Social Model. They assume that AI will make life more difficult for people with disabilities. But is it inevitable that AI will make society worse?

Risk #1: Bias and Discrimination

I had a friend in high school who was a mathematical genius. He had a photographic memory for numbers and read calculus textbooks like novels. He’d already taken every math class our school offered, so he took college courses at the local university.

Despite his academic success, he didn’t get into nearly as many colleges as I’d expected. He received rejections from schools that accepted his lower-scoring classmates. After a while, a pattern emerged – many of these schools required in-person interviews.

My friend wasn’t just a genius – he was also autistic. Like many people with autism, my friend didn’t interview well. He was shy, fidgeted, and forgot to make eye contact. The average college admissions interviewer didn’t know much about autism or how to help him feel comfortable. They wrote him off as a a “bad fit” and moved on.

I hear stories like my friend’s all the time. Prejudice against neurodivergent people – and all people with disabilities – is depressingly common. Will AI help us overcome bias, or will it make discrimination worse?

Bias has long been a major concern for AI researchers. Timnit Gebru was fired from Google in 2020 for sounding the alarm on AI’s potential for discrimination. Study after study has demonstrated that AI picks up biases from its training data.

In an oft-cited study, Amazon tried to automate its hiring process in 2014. They hoped an algorithm could quickly sort through a pile of resumes and determine the best candidates.

The results were disturbing. The algorithm discarded the resumes of qualified women in favor of male candidates. The program had been trained on the resumes of previous hires – and they were mostly men. Women have been underrepresented in the tech industry for a long time. Instead of helping Amazon overcome the gender divide, the algorithm solidified it. Amazon discontinued the program in 2018.

You can imagine how studies like this might make my friend anxious. He already struggles to get past a human interviewer. What if a bot trained on biased data learns to recognize autism? Would he ever get into college or offered a job again?

Risk #2: False Flags

People make mistakes, but so do machines. In Automating Inequality, Virginia Eubanks cites countless examples of machine-learning algorithms making catastrophic errors. For example, fraud detection algorithms flagged genuine insurance claims as suspicious, leaving patients in the lurch. Algorithms have also been used to deny Medicaid patients the care they need.

We tend to believe our machines. They seem rational and precise to us, unlike our squishy human feelings. So, when AI makes mistakes, we don’t always catch them. The people the algorithm harms are left to fend for themselves. The burden of proof falls on them, not the AI.

The implications of Eubanks’ book are frightening for everyone, but especially for disabled people. As AI tools become standard in hospitals and insurance companies, disabled people risk setting off algorithmic alarms. If a person with chronic pain asks for relief too many times, they might get flagged as a drug seeker. If their doctor doesn’t file a claim correctly, they might be denied insurance payouts.

Disabled people have to interact with the healthcare system more than the average person, making them more likely to run into problems. The consequences of being denied essential care could be disastrous.

How Dangerous Is AI, Really?

I want to take a moment to acknowledge the warnings in the studies above. There are real dangers to deploying AI irresponsibly. We must also be wary of our tendency to trust machines too much. We risk taking AI at face value, ignoring the possibility of bias and discrimination.

Does this mean we should stop using AI? Should we shut it down, like some researchers want to do?

I don’t think so. These scary studies get cited frequently, but most of them are old. They focus on a previous generation of AI models, mostly traditional machine-learning algorithms. Eubanks’ book came out in 2018. In 2024, AI Snake Oil cited many of the same studies. Six years of innovation hadn’t changed the talking points.

Bias, discrimination, and false flags are serious problems, but it’s hard to tell how serious when researchers tout the same last-gen studies. AI has evolved since then, and today’s LLMs are more sophisticated than anything Amazon used in 2014. We need new research that explores these issues in light of today’s technology. Citing a ten-year-old paper is not the end of the discussion.

Meanwhile, companies like Anthropic work hard to align their AI models for the good of humanity. Safety and non-discrimination are important considerations in designing new models. People are aware of the risks, talking about them, and looking for solutions. The existence of a problem doesn’t mean it won’t get solved.

The Limits of Our Imagination

Conversations about AI risks make a classic mistake – they assume tomorrow will look just like today. Faulty hiring algorithms are only a problem if we assume business will continue as usual. Bots auto-denying insurance claims don’t matter if we rebuild the healthcare system from the ground up.

It’s hard to wrap our heads around how much AI can change our lives. This technology is powerful enough to upend deeply entrenched institutions. That’s a scary thought, but it doesn’t have to be. Deployed with intention, AI can help us fix the problems that plague our society.

AI systems like Alphafold stand to revolutionize all of medicine. What if we could create a vaccine for every illness? What if we use algorithms to streamline our bloated healthcare system so everyone gets the care they need?

This vision might look too utopian for some of you, and that’s okay. Still, we must acknowledge that our society is at a crossroads. We’re developing a powerful new technology, but we haven’t deployed it widely yet. Instead of trying to stop AI, we should take this time to think critically about how to use it for the greatest good. That means all of us, disabled or not.

If you care about AI and disability, get involved and advocate for the change you want to see. We need more disabled voices in this conversation.

AI Is for All of Us

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. We’ve looked at two different models of disability, balancing risk and reward. We’ve seen how AI can help and harm both individuals and society. The future will probably hold a little of column A and a little of column B – some good and some bad, some personal wins and losses, and some societal ups and downs.

If you only take one lesson from this essay, I hope it’s this – AI is for you. I don’t know what tomorrow will look like, but you can use AI to help yourself today. If you have a disability, use it to empower yourself. If you want to advocate for social change, use it to suggest actions and draft policy.

After months of tracking my sleep with a chatbot, I’m starting to feel better. I’m still tired, but my mind feels clearer. My sleep score creeps up week after week. For the first time in fourteen years, I feel hope. I plan to keep using these tools for as long as it takes to get better.

Editor’s Note

We’re all human beings, and however we suffer (part of the human condition I am told), the techno-optimists say that AI can help, of course it could also make it worse – before it makes it better.

One of the reasons this publication will be presenting more guides, AI education and discovery of AI tools is because we want to, I want to, empower my readers to discover solutions that make sense for them.

Support independent journalism and curation that is not Billionaire owned or influenced. For less than $2 a week:

Read More in AI Supremacy